People will often use the different parts of ammunition interchangeably. For example, it’s not uncommon to hear some refer to an entire assembled cartridge as the “bullet.” That’s not accurate, however. Add in different types of shotguns shells and calibers, and the shooting novice quickly becomes confused.

The basic parts of ammunition include the bullet, cartridge case, powder, and primer. That’s for metallic ammo. Shotgun shells have slightly different components that we’ll also look at.

Ammo Confusion

Between the pandemic and civil unrest, the past couple years have been pretty bumpy. One result has been a huge spike in first-time firearm purchases. As for how many, figures I saw indicated three million first-time gun buyers during 2021 alone, nearly half of whom were women.

I’m guessing many of these new gun owners have some common concerns. Beyond initial worries over safety and security, firearms themselves could be entirely foreign – in which case, we might as well add ammunition to the list.

Where to turn? Crusty old gun cranks (like me) can stroll into just about any gun store as if they own the place. Between staff behind the counter and customers on the floor, an in-depth firearms discussion is almost guaranteed. By contrast, I can only imagine how intimidating the first trip would be for a newbie (not intended as a derogatory reference).

Bellying up to the counter would be mostly a leap of faith with no guarantees of a safe landing. If the interest is defense, those from either side of the counter will be quick to offer advice on a suitable firearm – more than likely a handgun in one of several popular calibers. Conversations tend to focus on desirable features, whereas ammunition often gets no more than passing mention.

The extent of it could be advice to skip a .380 ACP in favor of a 9mm; perhaps useful – if their differences are understood. It’s an easy trap to fall into for us gun people. We rattle on about good calibers and bullets while our audience is left to ponder the difference between a caliber and millimeter.

On top of that, not everyone is interested in a handgun. What about rifles and shotguns? Between defense and sporting uses, the list of calibers – and gauges – is almost overwhelming. And, things can end badly with wrong combinations.

So, here’s a time-out on firearms for a rewind to ammunition basics. Rather than start from scratch I’ll dip into my own book, Survival Guns: A Beginner’s Guide, one of several books in a series devoted to survival-based firearms.

- Markwith, Steve (Author)

- English (Publication Language)

- 106 Pages - 08/18/2014 (Publication Date) - Prepper Press (Publisher)

Ammunition Some ABCs

As noted above, gun people tend to speak a language all their own. Calibers and such being an integral part of most firearm discussions, the assumption is that everyone will understand a reference to a “twenty-two.”

But what do numbers like .22, 9mm, .30/06, or 12-Gauge actually mean?

To help sort things out, let’s break ammunition into two categories, metallic cartridges, and shotshells.

Metallic Cartridges

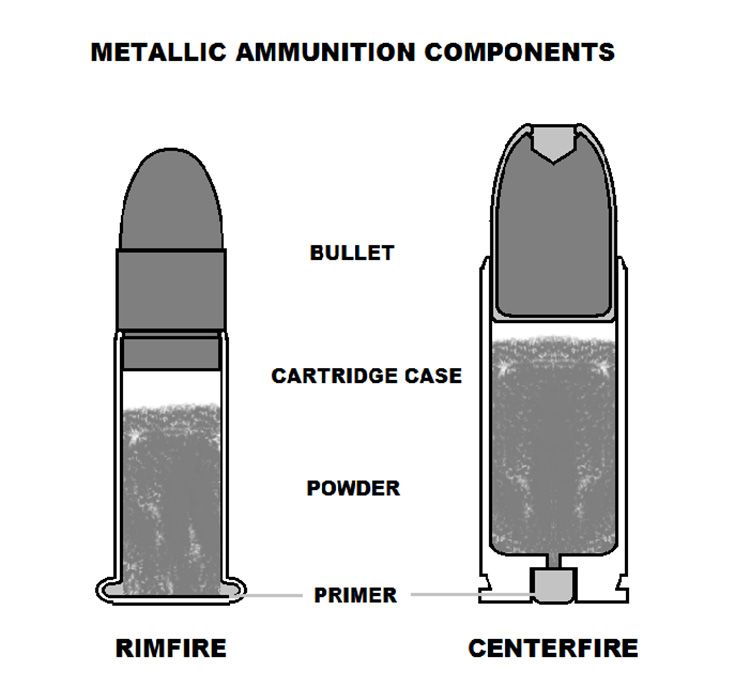

The .22 Long Rifle (.22 LR) and .30/06 are two of many metallic ammunition calibers. Although both have much in common regarding overall design, their ignition systems (known as primers) differ greatly. The .22 LR is a “rimfire” cartridge. The 30/06, along with other high-power rifle and defensive handgun cartridges, is a “centerfire.”

Shotshells

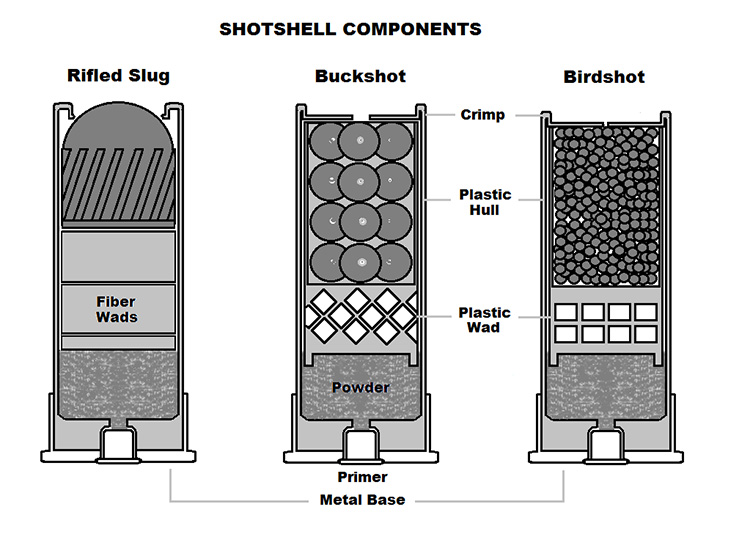

The 12-gauge is an example of a shotshell, and understanding their components is important if you ever want to try reloading shotgun shells. Like other “gauges,” although ignited via a centerfire primer, the greater portion of its cartridge casing, the shell, is typically non-metallic – as in plastic. Also, shotshells are designed to fire multiple projectiles (shot pellets) instead of bullets (one exception being slugs).

Basic Parts of Ammunition

Let’s start with the hugely popular .22 Long Rifle and work our way up. Relative to most other cartridges past and present, the .22 LR is a small cartridge that generates little noise or recoil. And, like other metallic designs, the “cartridge” itself is composed of four key components.

Bullet

This is the actual projectile. Most bullets are made from lead, a dense and malleable material. The bullet may, or may not, be encased in a thin copper jacket (like a “full metal jacket”). Its diameter will normally be expressed in “calibers”, and its weight will be measured in “grains”.

A .22 bullet is normally plain lead, although it may be coated with a very thin copper wash. More potent high-velocity loads utilize a thicker jacket to prevent accumulations of lead inside the barrel. The profile of a bullet and/or its jacket can prevent or promote expansion in a controlled manner.

Cartridge Case

Normally made out of brass, the case serves as a container to hold the bullet and a powder charge. Upon discharge, its ductile walls can also expand to contain rearward pressure. Once the bullet exits the barrel, the case shrinks a bit to allow extraction. A .22 Rim-fire case is made from very thin brass and, due to its priming design, it’s disposable upon firing.

Larger center-fire cartridges develop greater pressures, and are necessarily much thicker. Depending on their priming system, they may be salvageable for reloading with new components. Some ammunition is made with aluminum or mild steel cartridge casings. They’re more affordable, but non-reloadable.

Powder

Otherwise known as propellants, modern “smokeless” powders rapidly burn – instead of simply exploding. When confined, ignition produces high-pressure gas, expelling a projectile with great force. There are many types of powders and they burn at different rates suitable for various calibers.

These smokeless types should not be confused with original “black powder”, used for ten centuries. It behaves more like an explosive, emitting large volumes of corrosive, sulfurous smoke. Our more efficient and non-corrosive smokeless powders appeared during the late 1800s, and quickly supplanted black powder. Today, use of black powder is primarily confined to period-piece firearms.

Primer

This small explosive charge is located in the rear of the cartridge and, when struck by a firing pin, the resulting flash ignites the main powder charge. In our aptly named .22 “rimfire” cartridge, a priming mix is spun into its annular rim. A blow from the firing pin pinches the brass rim against the compound, causing detonation.

A centerfire cartridge contains a separate primer located in the center of cartridge base. The American “Boxer” design is self-contained, lending itself to reloading. The European “Berdan” system works differently and is difficult to reload.

Shotgun Shell Differences

Although the ammunition has similarities, shotguns typically fire multiple projectiles. Thus, the ‘bullet” is a payload of pellets contained within a plastic wad-cup. The “cartridge” (which runs at comparatively lower pressure) is usually a thin-walled plastic tube supported by a metal base. Ignition is produced via a larger “battery cup” primer, and the “shells” can often be reloaded.

While metallic ammunition is cataloged by calibers (or millimeters), shotshells are sized as gauges, 12-gauge being the most popular. A 10-gauge is bigger and the 16, 20, 28 & .410-bore are smaller. In fact, the .410 isn’t really a gauge at all.

What About Calibers?

Think “size.” Although the uninformed will sometimes refer to a loaded cartridge as a bullet, they’re really just describing one part. An assembled cartridge is commonly referred to as a “round.” Other terms quantify its type, size and capabilities.

Caliber (Cal.):

A caliber equals one one-hundredth (0.01”) of an inch. A .22-caliber bullet is therefore roughly twenty-two one hundredths of an inch (0.22”) in diameter. I use the term “roughly” because great license has been used by firearms manufacturers when labeling new cartridges. There are plenty of different .22-caliber cartridge listings in both rim-fire, and center-fire persuasions. The true diameter may vary from its label.

The most popular rim-fire load is the .22 Long Rifle (.22 LR). Its true diameter is 0.0223”.

The hotter .22 Magnum measures 0.0224”, and uses a longer, straight-walled case of greater diameter. These rounds are similar in design, but not interchangeable (although a few revolvers are sold with both cylinders). Firing a .22 LR in a larger-diameter .22 Magnum (WMR) chamber is unsafe.

The more powerful .223 Remington uses a somewhat heavier bullet of the same .224” diameter, but has a larger, bottle-necked case of center-fire design. The similar M-16 cartridge is known as a 5.56mm, but should not be fired in a .223 Remington chamber (related to higher pressures).

A .30/06 is much larger but is but one of many thirty-caliber cartridges firing a .308-diameter bullet. Here’s where things get strange: the ’06 refers to the year this round was adopted by the U.S. Army. It’s also called the “ought-six”, or .30/06 Springfield.

The .308 Winchester fires the same diameter bullet to similar velocity, but is a shorter and more modern version (also designated as 7.62×51 NATO for military use).

A .38 Special really measures 0.357”. The famous .357 Magnum is a longer version, loaded to higher pressure. You can safely fire a .38 Special in a .357 Magnum revolver, but not in reverse order.

The whole thing can be very confusing and, since most loads are not interchangeable, you can get in serious trouble by firing an incorrect round. If in doubt, check first with a trustworthy source!

Millimeter (mm):

The metric cartridge system is much more logical, although still imperfect. One millimeter (mm) equals roughly four calibers, so a 9mm is approximately .36-caliber (.355). The question is which 9mm? There are several to choose from.

The very popular 9mm Luger is a 9x19mm, and the second number refers to the length of its cartridge case. It’s different than the shorter 9x17mm, otherwise known as a .380 ACP (or 9mm Kurz).

As noted above, in military parlance, the .308 Winchester is a 7.62×51 NATO round.

The smaller Soviet load is a 7.62x39mm Russian (which actually fires .311 bullets).

The 5.56mm NATO will fire .223 Remington ammo, but as previously mentioned, the reverse may be unsafe.

Again, you need to be sure of what you’re firing!

Grains

We can use this unit of measurement to quantify the weight of a bullet (not be confused with individual grains of powder). As a unit of weight, there are 7,000 grains in a pound and 437.5 grains in an ounce.

- A standard .22 LR bullet weighs only 40 grains.

- A 55-grain military 5.56mm bullet is just a bit heavier, but travels at much higher velocity.

- A common 9mm bullet weighs 115-grains, whereas a .45 ACP is double that, or 230 grains.

- High-power rifle cartridges like the .30/06 Springfield or .308 Winchester often use bullets weighing 150 grains or more, but fire them at much higher velocities.

- A standard 12-gauge shotgun slug (which is a .73-caliber bullet) weighs an ounce.

More mass may mean more terminal punch, but velocity is also important.

Shotgun Gauges

The old English gauge system is used to quantify the internal diameter of shotgun barrels. “Gauge” is determined by the number of round, lead balls that will squeak through a barrel and equal one pound. In the case of a 16-gauge, the number of lead balls is sixteen, meaning each will weigh an ounce. For that reason, shotgun payloads are expressed in ounces rather than grains.

- The “payload” is a column of shot pellets, ejected as an expanding swarm.

- A standard 16-gauge shell throws one ounce of shot.

- The larger, highly popular 12-gauge standard load is 1 1/8 ounces.

- The smaller 20-gauge standard is 7/8 ounce.

These weights now vary considerably, and many 12-gauge loads approach 2 ounces. Shotgun shells are listed by length, with 2 ¾” being common. The 16 is now semi-obsolete, whereas the 20 prospers. Development of heavier, 3” magnum payloads account for the decline of the bigger-bore “sixteen.”

Cautionary Notes

Inserting a loaded cartridge (or shell) into a firearm is often described as “chambering” a round. Most barrels are stamped to indicate the correct caliber, millimeter, or gauge. AND a correct match is required to contain the extreme pressures generated upon discharge.

As noted above, if uncertainty exists regarding the correct chamber and ammunition, play it safe and hold your fire! This also pertains to any magnum versions. Just one example; a live 3” Magnum shotgun shell may fit in a 2 ¾” chamber, but upon discharge, the crimp won’t have anywhere to go – raising its already greater pressures through the roof (in this case the surrounding steel)!

For this reason, most ammunition boxes show the necessary information: caliber (or millimeter/ gauge), projectile weight, and its design. The info could be spelled out, or cryptically abbreviated.

Jacketed hollow points versus full metal jackets can also cause confusion.

- An FMJ? It’s a “full-metal jacket” bullet, typically made from lead, and encased in a thin copper sheathing.

- A JHP is a “jacketed hollow-point” similar to an FMJ, but with a cavity in its nose to promote expansion.

Parting Thoughts – for Now

Worth noting for future discussion, a bullet must be suitable for its intended task whether plinking, hunting, or defense. Beyond the actual caliber its design, mass, and velocity should be major determinant factors.

Meanwhile, many ammo manufacturers publish charts with useful data for their various offerings. The listings (by caliber) usually include muzzle velocity, muzzle energy, trajectory, wind-drift, and recommended sight-in ranges. The charts are worth exploring, and they’ll also provide a basic understanding of trajectory.

If interested in detailed information about firearms (or airguns) and ammunition, see my entire book series for more information.

Steve Markwith’s Books on Amazon

2 comments

excellent article Thanks

Great Reference article. Glad to see the site active!