The “ice city” in Italy of World War I is a lesser known topic in the history of this war. However, it’s also one of the more interesting ones. It is a story of survival under exceptionally harsh conditions.

“The Great War differed from all ancient wars in the immense power of the combatants and their fearful agencies of destruction, and from all modern wars in the utter ruthlessness with which it was fought. … Europe and large parts of Asia and Africa became one vast battlefield on which after years of struggle not armies but nations broke and ran. When all was over, Torture and Cannibalism were the only two expedients that the civilized, scientific, Christian States had been able to deny themselves: and they were of doubtful utility.”

– Winston Churchill The World Crisis, 1911-1918: Chapter I (The Vials of Wrath) (1923)

World War I and Ice City

During WWI, the necessity to establish and maintain an outpost in a crucial position was a necessity to winning battles. Geography played an important role in the fluidity of those battles, particularly in the Alps. Fighting in these alpine areas of Italy became known as the White War due to the constant and struggling presence of snow and ice. The harsh elements of this region turned to be an additional, harsh enemy to defeat.

This is the story of an outstanding effort to create and maintain an outpost at 3343 meters (10,967′) of altitude.

A Brief Overview

World War I (First World War or the Great War) began on July 28th, 1914 and lasted until November 11th, 1918. Centered and fought in Europe, it involved more than 9 million combatants and caused 7 million casualties, turning out to be one the deadliest conflicts in history. It paved the way for a series of major political changes and ultimately – revolutions.

The conflict, raised soon as global war, saw the Allies (the Triple Entente of the United Kingdom, France and the Russian Empire) against the Central Powers represented by Germany and Austria-Hungary. Later, more nations would enter the war, redefining the protagonists: Italy, Japan, and the United States joined the Allies; while the Ottoman Empire, along with Bulgaria, joined the Central Powers (Quadruple Alliance).

The White War

The expression White War (in German Gebirgskrieg, which can be translated in “war in the mountains“) identifies the specific scenario and setting of the tactical strategies and events that occurred in the Alpine sectors (Italian front) during the First World War. Between 1915 and 1918, the Dolomites turned to be the operational sector, as the troops of the Kingdom of Italy were opposed to those of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

This front was characterized by battles fought in medium to high altitudes above 6561 feet of altitude, up to the Ortles Mountain Group along the southern border of the historical region of Tyrol. This formidable, harsh, and natural obstacle was highly exploited by the Austro-Hungarian Army. Being outnumbered by the Italian army during the very early stages of the conflict, they made the decision to withdraw to the peaks, which happened to dominate quite all of the strategic points needed to take advantage of the elevated positions.

Since the very first months, the Alpine front began to become more static, leading to the establishment of well-fortified lines that filled every single gap along the front. Even the highest peaks were occupied in order to create a continuous and inaccessible battle line intended to be held month or even years.

Surviving and Fighting in the Alps

The toughest issues that the armies engaged in on the Alpine fronts were those related to the impervious nature of the terrain (mostly craggy) and the extreme climatic conditions. The three main mountains have altitudes on average higher than 6000 feet, making them extremely hard to travel across. The further you began to move from the valley, the more transportation was necessary in terms of packing animals. Mules, and even men, especially on narrowed passages, had to carry very heavy loads of artillery materials.

Only with the progress of the conflict over the years did a dense network of roads, mule tracks, and paths become created. Such was the reality of reaching outposts in the most inaccessible places. In the last two years of the war, the use of cableways was finally systematized, but the very construction of these infrastructures, roads and cableways, was perhaps the undertaking that required more energy and sacrifices in this particular front.

On the highest peaks, the temperature variations were noticeable. Above 8200 feet, temperatures below zero were quite normal even in summer, and it snowed – often. In winter, the thermometer can drop several tens of degrees. During the White War, the temperatures recorded were lower than 28° F below zero. The climate could change quickly and storms were present through every season.

In addition, the winters of 1916 and 1917 were among the snowiest of the century. The slopes of the mountains were covered by layers of thick snow, even three times more the annual average. Obviously, all these factors made life extremely difficult for the troops to live at high altitude. It was no more a matter of life, but survival. The constant presence of snow and ice forced the men to continually excavate and clear openings and spaces. This led to an increased risk of avalanches.

Related, the post-war historian Heinz Lichem von Löwenbourg stated: “On the basis of unanimous reports from fighters of all nations, the approximate rule applies that in 1915-1918, on the mountain front, two thirds of the dead were victims of the elements (lavine, frostbite, landslides, colds, exhaustion) and only one third victims of direct military actions.“

Constructing The City of Ice

The Great War was indeed a period of cutting edge strategies and innovations. In fact, in order to catch the enemy by surprise and conquer even just a few meters on the defense line, generals and soldiers had to use the most innovative means and weapons for the time, also resorting to the most ingenious strategies.

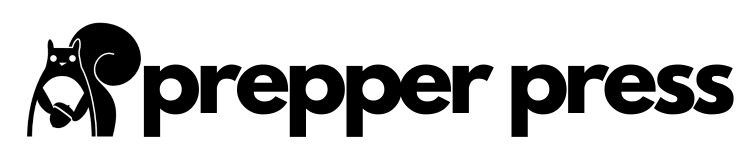

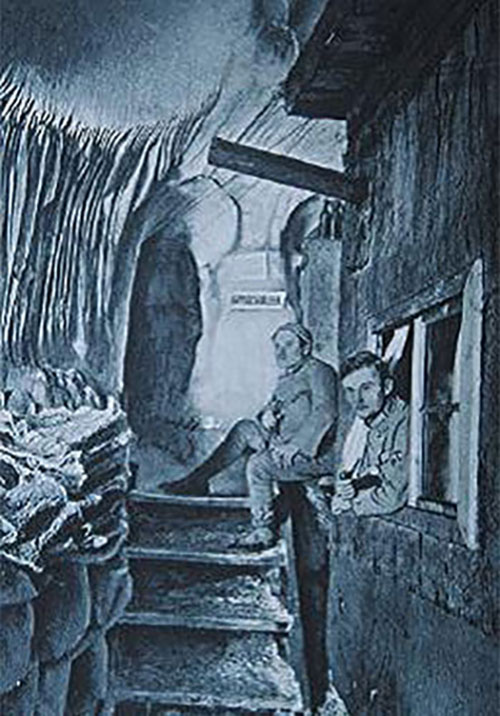

An example? The Eisstadt, ‘City of Ice’, conceived and layered in 1916 by the Austrian Lieutenant and engineer Leo Handl. The construction began a few months later. The City of Ice happened to be an extraordinary system of tunnels and passages dug into the ice with the purpose of obviating the danger of external walkways, which had proven to be too exposed to machine gun fire and avalanches. The idea of creating a City of Ice dawned on Handl during a night in May 1916.

Together with six other men from the Austrian army, Handl committed to defend the Marmolada Glacier. In order to escape the fire by the Italian troops stationed along the Seratura Ridge, they started to descend in a crevasse. Handl was passionate about mountaineering and, once at the bottom of the crevasse, he discovered he could exploit the space below the surface to advance more rapidly towards enemy positions while staying sheltered both from bullets and adverse weather conditions. The temperatures inside the caves swung between 32°F to 41°F, much more tolerable than staying outside on the top of the glacier.

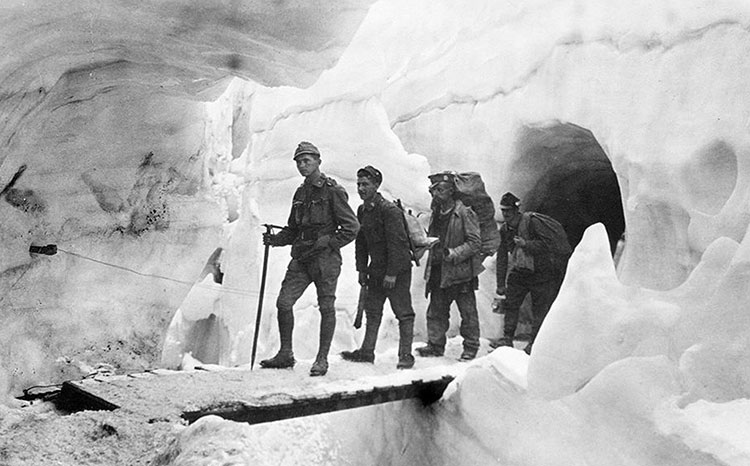

Handl thus began to forge the idea of building a real fortress made of corridors developed up to 7.5 miles at a depth of 197 feet, set as a temporary home for nearly 200 soldiers, which could host dormitories, kitchens, infirmaries, radio rooms, a chapel, cafeteria and safe places to store munitions.

The soldiers even brought power to the City of Ice from the small village of Canazei, located 6561 feet below. It was certainly very tough to live in that underground city, dominated by humidity and fear of being swallowed by the ice. Nonetheless, Handl’s idea indeed saved many human lives and remained a real stronghold. The City of Ice remained active until the defeat of Caporetto, which meant the consequential shift of the front to the southern position. Later on, the City of Ice was abandoned.

Ice City Today

With the melting of the great Marmolada glacier, many find tools and other objects of that period as they are brought to the surface. They are now preserved inside the Marmolada Museum, which is the highest museum location in whole Europe, located at almost at the impressive altitude of 9482 feet above sea level.

Nowadays, only a small amount of outstanding materials tell us the incredible story of the City of Ice. In fact, when the soldiers started to abandon the Dolomiti’s front, the ice tunnel which hosted the City began to collapse and melt.

Only in recent times, have other items been found and brought to the museum after the glacier melts. Thousands of other pieces of equipment are buried deep inside the silent and sullen glacier.

While you won’t be able to visit the ice city as a tourist, as Derrick did with a WWII Nazi bunker, the history of it is interesting just the same.