You’re an avid shooter with limited time. How often should you clean your gun? Can you be too meticulous? What is necessary to prevent damage to the firearm?

Don’t clean them enough and they can get grubby bores and rust. Clean them too often and you risk damaging the barrel crown and rifling from a rod pushed down unnecessarily often.

Every person will have their own views on this subject. Mine are based on years of experience leading firearms training for a state agency.

How often you should clean your gun depends on personal choice, manufacturer recommendations, the firearm’s material, type of ammo fired, storage conditions, shots fired, and weather encountered.

There is no one-size-fits-all answer, unfortunately. However, my experience may serve as a guide.

Background Story

I’d just wrapped up another action-filled day with a friend, the second of our three-day prairie dog shoot. The small South Dakota motel that served as headquarters was a welcome sight, but as soon as we cracked our door we were greeted by the strong aroma of gun solvent.

The waste basket’s large collection of fouled patches had been replaced by a fresh liner and, within seconds, our room phone rang – not a good omen. Sure enough, the manager was on the other end. Expecting the worse, I was surprised by the conversation.

Turned out he was interested in a body count! I guesstimated our day’s tally was around three hundred prairie dogs. The manager’s response was, “Good, thanks, we hate em!” Whew…

Our gun cradle was still perched on the desk so we dragged in our hard-shell rifle cases. Two of them contained one-piece cleaning rods, and we’d packed an ammo can full of cleaning supplies. More solvent and patches flew, but by evening’s end, the barrels of our .223 varmint rifles were ready for another day of non-stop shooting.

Hopefully, the housekeeper tolerated the fragrance of Shooter’s Choice. If not, at least she got a decent tip.

A couple days and 2100 road-miles later, now minus several hundred rounds, I went to the home workbench for more through barrel care. An HB .223 Remington M-700 had been the busiest, and despite a nightly cleaning, I was betting on a fair amount of residual fouling.

That hunch was confirmed via more solvent and patches. Before declaring the process “done,” I switched to a few additional patches impregnated with JB Bore Compound. The first appeared as a gooey black mess, but the next few were progressively better. A trip to the range revealed the rifle’s accuracy had slightly deteriorated, but still averaged 0.6 MOA.

The next step was a return to the workbench for a final careful cleaning.

Whenever possible, I’ll baby a rifle that can drive tacks, seldom exceeding 18 rounds between each session. This practice seems to deliver consistent groups but it’s not always possible. And, for the most part, it’s really not necessary.

Cleaning Considerations

Round count is a significant maintenance factor, but it isn’t the only one. In a previous life, I was OIC of a governmental firearms training unit.

Between large inventories of agency firearms, and a separate personal collection, gun cleaning was neverending. Anything that could simplify the process was thus embraced, starting with basic storage methods.

Storage and Inspection

I’ve encountered few problems (almost none) with my personal firearms. A few deer rifles lurk in the nether regions of the gun safe for eleven months, however none suffer any ill effects. They’ll see their share of hard use during November, but they’ll also receive daily maintenance.

The key to their long-term health is a thorough cleaning in December, backed up with occasional inspections. These rifles have probably seen more hard use than the rest, as well as the longest downtimes. Fortunately, my safe is in a living area, so its interior environment is relatively stable.

However, it could be easily regulated via any number of purpose-built moisture control products. Long-term storage of firearms in soft-cases is something I avoid because some types can accumulate moisture.

Our agency’s concrete armory – an average size room – posed greater challenges. A rack full of well-used Remington Model 870 Police 12 gauge shotguns would start rusting each June when warm humid air arrived. The fix involved regular maintenance, combined with the seasonal installation of a dehumidifier.

A rack of AR-15s held up much better thanks to their aluminum receivers and mil-spec chrome-plated bores. Same for a bunch of polymer/stainless S&W M&P pistols.

Back in our revolver era, an inventory of S&W stainless M-65 revolvers stood up amazingly well although rust would eventually form underneath their grips. None of these issues were attributable to shooting. Instead, they related to handling.

Handling

Seems as though some people have gun-rusting digits. Others, not so much. Even without any residue of Doritos on my fingers, I always follow these two steps before a firearm enters the safe:

First, the gun is checked twice to ensure it’s unloaded!

Second, its metal surfaces are wiped down with a lightly oiled rag.

The last detail ensures ongoing protection regardless of the firearm’s metallurgy. Stainless steel is more rust resistant but it can still rust, and some alloys are less forgiving.

Weather

People who slip wet firearms into cases shouldn’t be surprised to discover speckles of rust. A rapid transition from cold weather to warm environments can produce the same effect, due to rapid condensation. The fix is relatively simple; purge water from nooks or crannies and perform whatever maintenance is needed. Believe it or not, I’ve used WD-40 on guns for many years with no problems.

Disassembly

Firearms that feature easy disassembly promote regular maintenance. Case in point, our agency-issued S&W M&P Pistols (could just as well be Glocks, etc.). Inspections reveal a higher degree of cleanliness than previous S&W 3rd Gen D/A versions, which were more “fiddly” to disassemble.

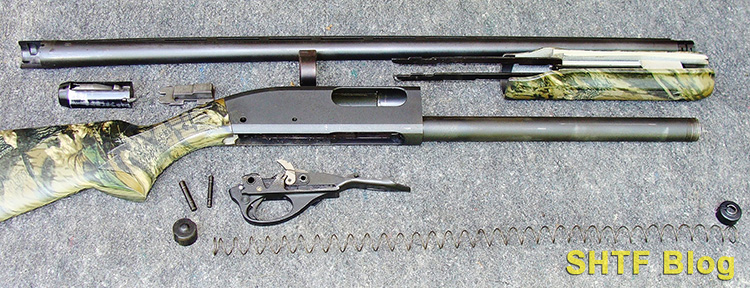

Most of today’s tactical Tupperware pistols can be field-stripped for routine cleaning within seconds, without airborne guide-rods or disappearing slide stops. Revolvers are even simpler. Pump shotguns or doubles and bolt-action rifles also offer easy maintenance.

Round-Count Examples

Onward to shooting! The examples shown below may work for many shooters, although there’s really no hard and fast rule.

Rifles

The majority of centerfire sporting rifles probably digest no more than a handful of rounds per year, but many of them still have grubby bores due to years of skipped cleanings. The flip side is an over-zealous approach, often using a jointed rod (sans bore-guide), that results in worn rifling and/or a dinged crown.

Somewhere, there’s a happy balance.

Using our three-day patrol-carbine program as an example, each trainee fired around 450 rounds. He or she started with clean AR-15, attended a training/cleaning introduction on day #2 , and wrapped up day #3 with a thorough maintenance session.

Many of our M-4 type 5.56 carbines have been through a number of these programs, but they’ll still run reliably, while holding sub 2-MOA accuracy.

Sometimes though, it only takes a few shots to cause mischief over time. Two examples coming to mind are a Ruger Mini-14, and a Winchester Model 100, both of which were solidly locked up due to corroded gas systems – easily preventable through a simple cleaning.

How about rimfires? Many of us shoot .22 LR by the brick between cleanings. Most plinker-grade rifles won’t suffer any real accuracy loss, but fouling build-up will lead to inevitable stoppages and also a possible hazard. Semiauto .22 LRs employ non-locking, blow-back bolts.

If the bolt isn’t fully seated because of thick deposits, the rifle might still fire, expelling hot gas and brass fragments. That’s why we wear shooting glasses – and should also do some cleaning.

How often? No set rule, but my semiauto rimfires are cleaned well before the 1000-round mark.

Shotguns

Our armory-issued M-870 pump-guns showed hard use, but their innards were squeaky clean. They were also part of a larger inventory. To help spread wear, a different batch was assigned to the range each year for training purposes.

Weekly ammo consumption averaged around 250 shells per gun; a mixture of 2 ¾” target loads and buckshot with a smattering of slugs in the mix. These guns received daily wipe-downs and one thorough cleaning each Friday (see note), a practice that kept them running for the week.

At the end of the year, they were all detailed cleaned and rotated into service or reserve status.

Note: Plain lead Foster-type slugs are much less forgiving, and can quickly smear a bore with lead.

Nowadays, I shoot mostly semiautomatics, consisting of Beretta’s gas-guns. I won’t let one sit for too long regardless of its shell consumption, but if the weekly total is around 50 shells, it’ll get a good cleaning every other week. Each will also receive a thorough post-season cleaning to include detailed disassembly.

Many shooters stretch their autoloaders a lot further. Some will also experience malfunctions that appear like magic in duck blinds. Folks less dedicated to regular cleaning may benefit from inertial autoloaders, pumps, or double-guns.

Whatever the choice, don’t forget those choke tubes. If the threads aren’t cleaned and re-lubed, they’ll eventually fuse to the barrel!

Handguns

Our basic pistol program followed a similar format to the patrol carbine course, incorporating two cleaning sessions. However, ammo expenditure was greater at 750-plus rounds per shooter over five full range days.

No doubt, we could have saved cleaning for the end, but the familiarization-block would’ve been lost – and its omission would have been a bad example.

The doubt factor is real, too. Stoppages encountered with dirty pistols undermine confidence in a system, even though many are shooter-induced. The initial cleaning was timed to precede a night fire and included removal of carbon from night sights. Because some solvents can attack the Tritium seals, this step was performed with a cloth.

The magazines received similar attention, minus dirt-attracting lubes (don’t use too much!). A similar routine served us well during week-long basic revolver programs. Spots that needed cleaning included the faces of the barrels and cylinders, along with the undersides of extractor stars.

Some handgunners go a lot longer between cleanings, but for us, another big concern was system life. Metal-on-metal parts tend to suffer less wear when their surfaces are clean and lubricated.

Muzzleloaders

Guns that burn black powder (or several similar substitutes) should be cleaned ASAP – even after just one shot! The residual fouling will quickly attract moisture, leading to rust within hours; almost certainly, overnight!

A Few Concerns

A firearm earmarked for defense should get a thorough on-range shakedown. Using a semiautomatic pistol as an example, I’d hope to fire at least two hundred rounds (using each magazine), to verify reliable function. Double or triple that amount would be a safer bet, but of course, ammo is scarce and expensive.

Still, if reasonably possible, it’s worth shooting at least two boxes of a chosen defensive load. Assuming everything checks out, the next step should be a thorough cleaning, followed by lubrication per the factory’s guidelines.

Periodic maintenance is equally important. Lint or dust will gradually accumulate, and lubricants can gum up or evaporate, eventually causing stoppages. Today’s optical aiming systems will also require attention along with periodic battery exchanges.

Defensive ammunition should also be inspected and cleaned as necessary- but skip solvents or lubes. Some types can contaminant powders and primers!

We replaced our service rounds each January and saved the old stuff for night-fires. The better option; unload your magazines through some shooting. If applicable, this is a good time to replace an optical sight’s battery.

Safety

First, the obvious! Prior to performing any maintenance, unload in the safest area available. Then check the gun at least twice!

Also, because it’s better to be safe than sorry, isolate any live ammo from the cleaning area.

FYI, the kitchen table is a poor choice. Lead residue is a real concern for everyone, especially for children. Further hazards include spring-loaded parts and caustic sprays. Soap and water will remove lead from hands and safety glasses can protect our eyes.

Final Thoughts

Cleaning regimens vary considerably because of firearm designs and personal preferences. A double-action revolver is fairly basic, but it could easily constitute an entire “how to” post.

For what it’s worth, the firearms we selected for service use were first well-vetted via copious amounts of live rounds, combined with infrequent cleanings. One thing was certain though, regardless of rounds fired, no firearm ever entered service until it first received a thorough cleaning. That, and an ongoing maintenance regimen.

1 comment

A good article.

My cleaning goes something like this. I’ll clean any new firearm before I ever take it to the range. That gives me a chance to become a little more familiar with the firearm and inspect it better. After that…I run a bore-brush with a little solvent down the barrel after the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 10th and 20th shot. I give it a cleaning after every range visit and if I don’t take a particular firearm to the range, I will give it a quick going over every four months or so. Cleaning your firearm, many times, is a personal preference, but at a minimum I would clean it after every 250-500 rounds…maybe sooner, depending on the firearm as some just seem to get dirtier, faster and some ammunition tends to be dirtier or doesn’t burn as cleanly as some other brands.

If you do shoot black powder firearms…clean them ‘very thoroughly’ after using them, regardless of the powder used. I’ve seen several, very nice, black-powder firearms that were ruined simply because the owner didn’t clean them.