Preppers naturally gravitate toward more common firearms like the 9mm pistol and AR-15 rifle as their choices for the best survival guns, and for good reason. But what about other firearms, whether for survival, hunting, or hobby? Here we explore how to load and shoot a flintlock rifle. If you haven’t owned or shot one before, maybe you will find them as fun as I do.

If you feel inspired to try one out, the Traditions Deerhunter Muzzleloader Rifle with 24″ BBL comes with a price that won’t break the bank. It’s available at Natchez and, if you’re shopping there, install the Rakuten app for an extra 1% in cash back.

As for the “prepper” aspect of them. You can order them by mail and light it with a rock. Does it get any easier than that?

Expanded Hunting Season with Black Powder

This past November’s deer season a nice eight-pointer was piled up at my feet. Normally, our legal limit is one deer per year. This one would certainly refill the freezer, so I scratched off the remainder of our November rifle season. BUT, a rare bonus doe-only tag was still tucked in my wallet.

By Thanksgiving, a couple muzzleloaders were gaining daily appeal, inspired by an extra two-week black powder season slated for December. The front-stuffers had seen some use by others in my circle but I’d never reached that point.

A lonely flintlock rifle at the rear of the safe presented a great excuse to get back in the woods so I finally dragged it out. The main objective was more about the process than the outcome since any deer taken would have to be small.

Flintlock Rifles – A Short History

Flintlocks appeared in the early 1600s as evolutions of previous designs. Revolutionary at the time, they reigned supreme for two centuries until rendered obsolete by a simple metal cup. However, the actual loading process remained, for the most part, unchanged.

The propellant was still black powder. A loose charge was introduced through the barrel’s front end (its muzzle), followed by a projectile. Both were then driven home with a ramrod. By the 1820s the source had evolved to the above percussion cap, placed over a hollow nipple with a pathway to the barrel.

Prior to that breakthrough (which eventually led to today’s cartridges), a separate priming charge was required, along with a mechanism that could generate the spark.

How a Flintlock Rifle Works

Quick version: A flintlock rifle involves a piece of flint striking frizzen, creating sparks, igniting black powder, and propelling the projectile out the muzzle.

A flintlock starts with a rock – literally. It’s a piece of flint, clamped between a set of steel jaws on a sturdy hammer. When fully cocked, the flint is poised above a small pan containing a separate charge of fine black powder.

The pan is covered by a spring-loaded steel cap with a large vertical ear called a “frizzen.” When the trigger releases the hammer, the flint impacts the bare-steel surface of the frizzen, creating a spectacular shower of sparks. Simultaneously, the integral cap is rocked open to expose the priming charge for ignition.

These fireworks are transmitted through a small port in the barrel (its vent) to the main charge. The discharge is exciting, and often accompanied by a delay, although the pause is often hyped. Actually, with everything working properly (including the user), it all happens pretty quickly – with lots of white smoke!

Advantages to Flintlocks

Firearms and ammunition are scarce and costly, with much new noise about impending regulations. Assuming you have the reloading equipment, even metallic ammunition components are now selling for absurd prices. The Feds don’t regulate muzzleloading guns (or modern airguns), so no FFL process is necessary (but check your local/state laws).

I bought my Lyman .50 Trade Rifle by mail. With primers and brass off the table, if need be, I could make my own bullets – and, maybe, even powder! Further plusses include extended hunting opportunities and a greater degree of social acceptance.

Disadvantages to Flintlocks

Flintlocks don’t play well in wet weather (although a few old tricks can help). And, of course, you’ll probably be limited to one shot because of the lengthy reloading process. Dirty hands and cleaning hassles are also part of the process since black powder produces lots of “fouling.”

It’s also hygroscopic so, unless cleaned ASAP, rust will quickly form. True black powder is also an explosive which tends to limit its availability.

I will say this: you may not draw a crowd with a tricked-out AR-15 or Tupperware pistol, but you probably will with a flintlock. Shooting these old-time boomsticks can be lots of fun! Want more entertainment? Buy a kit and “build” your own. Many are semi-finished and can be completed with basic hand tools for less cost.

Muzzleloading Evolutions

Regardless of their design, most of today’s popular muzzleloading rifles are .50-caliber. Unlike smoothbore “muskets,” they have rifled bores of various twist-rates suitable for round-balls, soft lead bullets, or sometimes, both.

Well into the 1800s, round-balls were the common projectile. Most military “muskets” were larger-caliber smoothbores which simplified loading as fouling accumulated (see Brown Bess). The tradeoff was poor accuracy which limited predictable hits on man-size targets to around fifty paces.

True colonial riflemen were a fearsome threat due to their rifled barrels. The projectile was still a ball, but it was sized to engage the grooves while wrapped in a tightly fitting patch. Although slower to load, accuracy greatly improved, permitting hits out to 200 yards. The downside was a slower rate of fire.

By the Civil War both sides were using rifled muskets which fired hollow-based conical projectiles. Today, variations of this system have made comebacks thanks to special muzzleloading seasons that can increase hunting opportunities while controlling burgeoning deer populations.

Although the loading process remains similar, progress has led to sub-caliber projectiles encased in plastic sabots. The propellant is often a facsimile sold in pelletized form, ignited by a shotgun primer. Effective, but not too “traditional,” especially when compared to a flintlock!

How Accurate is a Flintlock Rifle?

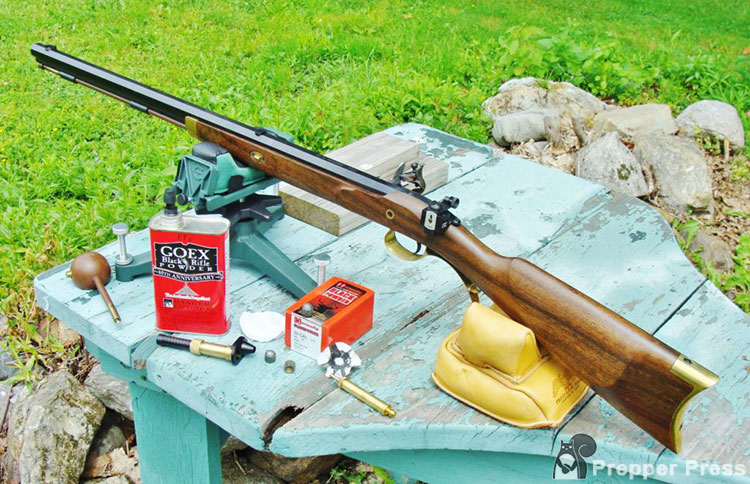

Round-balls shoot more accurately in 1:66 twist rates; too slow for stabilization of longer “bullets.” My Lyman .50 Trade Rifle is a modern compromise, rifled with a 1:48 twist. My flintlock rifle will shoot palm-sized groups with either projectile at 100 yards – good enough for me.

I zero it for 75 yards, using 240-grain lead bullets fired at around 1600 fps (a guess). Its 28-inch barrel is long enough for efficient combustion but short enough to carry afield. At 8 pounds it’s a handful, but the weight does soften recoil.

I replaced the fixed open sights with a Lyman M-66 tang-mounted receiver sight and green fiber-optic front (modified to fit the European .350” dovetail). Like a number of other such “reproductions,” the Lyman is built in Italy. Quality is quite good considering its price.

How to Load and Shoot a Flintlock Rifle

If you’re going to get serious about shooting flintlock rifles, consider picking up a copy of the Lyman Black Powder Handbook. It’s a reloading manual worth the money.

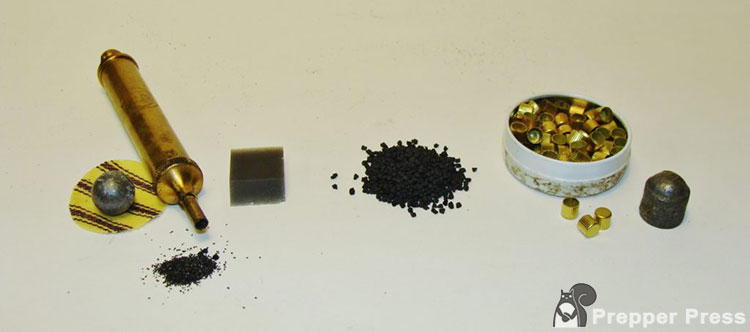

The basics of how to load and shoot a flintlock rifle starts with the components, and those include:

- a handy priming dispenser,

- a can of fine FFFF-G powder

- a coarser-grade powder,

- a powder measure, and – of course

- a projectile.

You’ll also need patches, a properly fitting jag for the rod, a touchhole pick, and (maybe) a ball-starter.

Regarding powder, several alternatives are sold, but not all are suitable for sparks. I use true black powder, available in granulations of F, FF, FFF, and FFFF-G. The choice for .50-caliber guns is typically FF, although I have used FFF-G (in slightly reduced quantities).

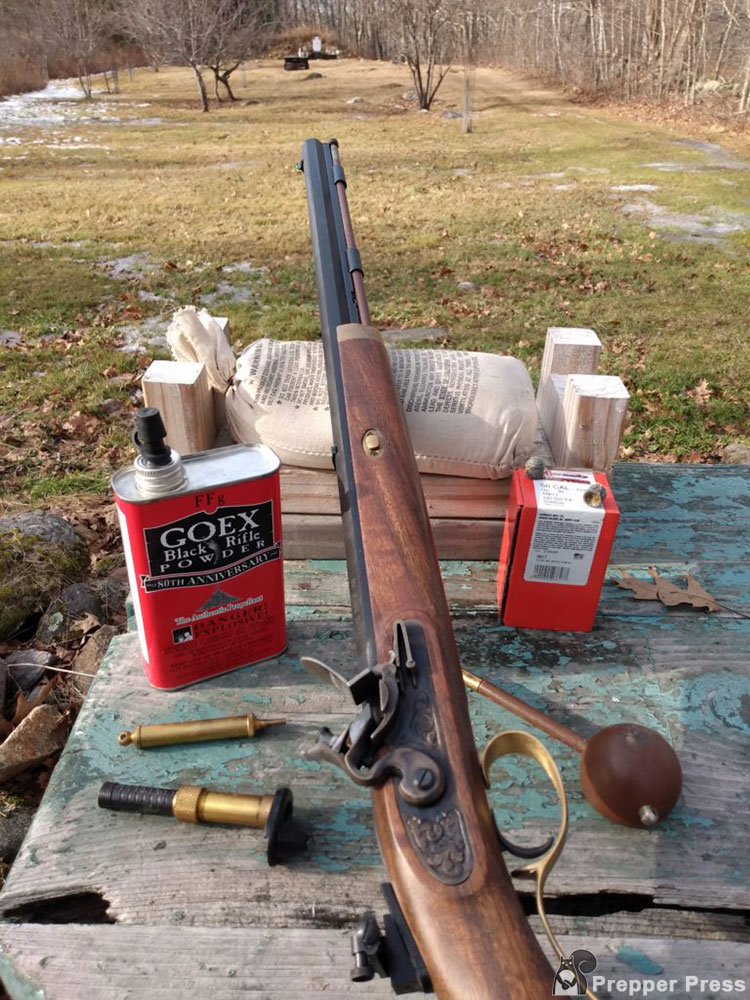

Fine four-F is for priming, although triple-F can work. To be safe, follow the rifle manufacturer’s guidelines regarding granulations and charges. Some die-hard afficionados swear by preferred brands. I shoot what’s available; in this case, GOEX.

Caution: Never use smokeless powders. Their much higher pressures will, at best, destroy the gun!

Loading a Flintlock

What follows is the method I used to load my Lyman Trade Rifle for the December deer season. Conditions ranged from cold to downright artic, and the last thing I wanted was a “flash in the pan” after two weeks of freezin’!

Preparation

Because black powder is hydroscopic, hot water is often used for cleaning, followed by a rust preventative – which can also kill powder. Owners of percussion systems solve this problem by firing a couple caps.

I used a liberal dose of Gun Scrubber which was swabbed through the bore using saturated patches on my ramrod’s jag. I also used some on the lock’s pan and frizzen. Next, I carefully un-cocked the hammer so the flint was resting in the pan, unable to generate a spark.

Charging

Black powder is typically dispensed by volume instead of weight. An inexpensive powder measure makes this easy. Most have a sliding mechanism with a graduated scale to set the volume in “grains.”

Lyman listed 100 grains of FFG as max for the 240-grain projectiles I was using but, through trial and error, I achieved better accuracy with less. After carefully filling the measure with 90 grains of FFG, its small sliding funnel was used to level off the charge. Next, it was poured into the muzzle, followed by a few taps to help settle the powder.

Caution: Never load directly from the powder cannister! One errant spark will blow you to kingdom come. It could also detonate an open container.

Projectile

Initially, I used patched round-balls of .490-caliber, seated in pre-lubed .010” pillow-ticking patches. Since a tight fit was required, pressing them into the muzzle required a ball-starter.

Today, I use Hornady’s 240-grain PA Conicals which are pre-lubed soft-lead bullets. They’re greasy (I wipe off the bases), but soft enough for me to start with my thumb. Other rifles may require a ball-starter. Most have a short leg to start the process, and a longer one for full rifling engagement. The starter is a must if loading a patch and ball.

Seating

The rifle’s ramrod finishes the job. Mine is an “unbreakable” aftermarket type with threaded ends that accept a jag, ball-puller, or patch-worm. Firm pressure is required (while keeping the business-end clear of body parts). A steady strong stroke is safer than repeated pounding. Once your load is established, you can scribe a reference line around the rod that coincides with the muzzle. It’ll ensure full seating, and help determine if the barrel is loaded.

Caution: Full seating is an absolute must!

Priming

Save this step for last! A pan primer makes it easy. Mine is a small brass vial with a spring-loaded spout. The hammer is drawn to half-cock, exposing the opened pan for priming. If the dispenser is held vertically with a finger over its tip, a push inward on its spring-loaded spout will fill the small nozzle with FFFF-G.

Release the spout and carefully distribute the charge in the pan. You don’t need a mountain; just enough for a level spread that needn’t enter the touchhole. Close the pan and you’ll have a loaded rifle!

Firing

To fire, fully cock the hammer. Prepare for some fireworks and smoke when the trigger is squeezed. Some follow-through is necessary but, as previously mentioned, any delay between ignition of the priming and main charge should be brief – assuming proper attention has been paid to the details!

Regarding triggers, some rifles have two. Pulling the rear “sets” the lock-work for a much lighter release of the front trigger (a so-called hair trigger). I prefer the KISS approach of a single trigger.

Caution: Keep body parts and bystanders clear of the rifle’s lock-work and touchhole!

Un-cocking

The technique follows other hammer-fired designs. The hammer’s descent is manually controlled as the trigger is pulled. One difference: You can clear the pan of powder.

Reloading

Fouling can make bullet-seating difficult, even after just one shot. Another concern is an ember in the barrel. The solution? Run a spit-moistened patch (or two) through between each shot.

Open the pan first to help vent the bore, and give the tray a quick wipe. Then, probe the touchhole with your small pick to free its passage. These simple steps are all I normally need to ensure reliable function.

Assembling a Kit

All-important patches should be sized to match your bore and jag (I use 2 ¼” round patches to clean my .50-caliber). A patch-worm and ball-puller are worthwhile ramrod accessories. The worm’s small fingers are designed to fish out an errant patch.

The ball-puller is a modified woodscrew, designed to penetrate a projectile loaded without powder. As for flints, I got dozens of shots from the original, which was used to size the replacements. The flint is secured between the hammer’s jaws with a non-flammable piece of leather, but lead chimney flashing also works.

The all-important vent tool can be anything from a dental pick to a paperclip. I bought a spare threaded vent-liner but, so far, haven’t needed it.

My gear, from Dixie Gun Works, travels in a traditional leather “possibles bag,” but some of its contents are modern. Several lengths of clear plastic gas-line tubing serve as speed-loaders (commercial versions are available). One end is plugged by a chunk of 1/2” wooden dowel to contain a pre-measured powder charge.

At the other end, a shorter section separates the powder from the lubed lead bullet. I simply bite off the large plug to pour in the powder. The bullet’s base protrudes a tad to start it in the muzzle. A stash of patches is stored in a plastic film container.

The pick hangs around my neck on a length of decoy line, along with the small priming gadget. It’s a handy pre-dawn grab & go setup.

How do You Unload a Flintlock Rifle?

Pure and simple, the safest way to unload a traditional flintlock is to shoot it!

That said, regulations vary state-by-state. In mine, a muzzleloader is considered legally unloaded (for purposes of transportation) if its priming charge is removed. BUT, you’ll still have a loaded gun!

Intentional or accidental contact of a flint against the frizzen could still generate a spark that could find the main charge.

Managing a “Loaded” Flintlock

I hunted mornings and evenings, mostly right out the back door on my property. After a cold hike home in the dark, priorities were a change of clothes, a fire in the woodstove, and a hot meal. Darned if I wanted to shoot and clean the flintlock knowing I’d be out again before first light.

Instead, I stored it unprimed in a case tagged “LOADED!” This package was stashed in my unheated (43F) walk-in basement – as far indoors as it ever went.

I primed the rifle when on stand, and simply wiped the pan clear of powder before leaving. At that point I installed a low-tech safety; a soft foam earplug pierced by a cocktail toothpick. The plug was nestled in the pan with the toothpick inserted in the vent.

The hammer was then gently lowered to hold it in place (sounds gross but an occasional swipe of body oils from behind my ear lessened concerns over a static spark). Once home, the rifle remained in its chilly environment to eliminate condensation.

The same technique worked well while hunting local spots, with the case in my truck and the heater on a low setting. The load was checked daily with the ramrod to ensure it remained fully seated.

As for a deer, I passed up a few perfect ala carte candidates without regrets (including three after loading the rifle). The experience alone was worth more than the unenviable title of “Bambi-Basher.” Three weeks later came the moment of truth when I set out a target to “unload.”

All doubts were dispelled from an energetic report and a well-centered 75-yard hit. I fired the spare loads as well. Everything working normally.

The temporary storage method was iffy, but our kids are grown and gone. Still, it never entered our living space and the basement was always locked.

Conclusion

Is a flintlock worth the bother? Heck, percussion caps are simpler. Then again, metallic cartridges are easier, still.

Nevertheless, some traditionalists use cap locks for the extra challenge. Thus, flintlocks are a logical extension. The process is involved enough that powder tends to last. Heck, firing ten shots is quite the adventure! It’s a dirty one as well, accompanied by the aroma of rotten eggs, thanks to a primary ingredient – Sulphur.

Speaking that, it’ll need to be cleaned ASAP. One reason I bought my Lyman was its easily removeable barrel. But, cleaning is a story for another installment.

Do you own a flintlock?

1 comment

There are several groups out there that can help. One is the NMLRA, National Muzzle Loading Rifle Association.

They can direct you to groups around the country. In Virginia I belong to the Virginia Muzzle Loading Rifle Association , they sponsor shoots around the state all year round.

https://www.nmlra.org